Facts and Details

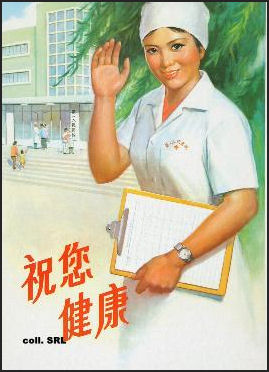

Improved health care was considered one of the great success’s of the Mao era. Barefoot doctors brought modern medicine and prevention strategies to places that had minimal health care. These and other Chinese health care workers are credited with 1) reducing infant mortality to a lower level than in New York City, 2) eradicating small pox and nearly eradicating sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis and schistosomiasis and 3) raising the average life span of Chinese from 35 in 1949 to 68 years in 1979. Many of China's health statistics are comparable with those of a much richer country.

Improved health care was considered one of the great success’s of the Mao era. Barefoot doctors brought modern medicine and prevention strategies to places that had minimal health care. These and other Chinese health care workers are credited with 1) reducing infant mortality to a lower level than in New York City, 2) eradicating small pox and nearly eradicating sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis and schistosomiasis and 3) raising the average life span of Chinese from 35 in 1949 to 68 years in 1979. Many of China's health statistics are comparable with those of a much richer country. In the Mao era everyone was covered by health insurance that was free or very cheap. Although the medical care was often less than ideal at least people were covered and if they did need hospitalization it wouldn’t bankrupt them.

In the Mao era everyone was covered by health insurance that was free or very cheap. Although the medical care was often less than ideal at least people were covered and if they did need hospitalization it wouldn’t bankrupt them. The cost of having a baby delivered at commune hospital in the 1980s was about $3. The state subsidized treatment for all kinds of illnesses. One Chinese factory told Reuters, "I never spent a penny. Often you’d be given a week's supply of medicine when you only needed it for two days. The rest you'd just throw away."

The cost of having a baby delivered at commune hospital in the 1980s was about $3. The state subsidized treatment for all kinds of illnesses. One Chinese factory told Reuters, "I never spent a penny. Often you’d be given a week's supply of medicine when you only needed it for two days. The rest you'd just throw away." In the 1950s, Mao launched a campaign to get rid of the snails that cause schistosomiasis by urging peasants to turn over soil in lakes and river beds by hand before the rainy season. People chanted slogans like "our strength is boundless and our enthusiasm redder than fire" and were inspired by banners that read "Empty the rivers to wipe out the snails, resolutely fight the big bell disease." The campaign came very close to eradicating schistosomiasis.

In the 1950s, Mao launched a campaign to get rid of the snails that cause schistosomiasis by urging peasants to turn over soil in lakes and river beds by hand before the rainy season. People chanted slogans like "our strength is boundless and our enthusiasm redder than fire" and were inspired by banners that read "Empty the rivers to wipe out the snails, resolutely fight the big bell disease." The campaign came very close to eradicating schistosomiasis.  Mao launched the program to kill the "four pests" (sparrows, rats, insects and flies). Every person in China was issued a flyswatter and millions of flies were killed after Mao gave the directive "Away with all pests!" The fly problem persisted however.

Mao launched the program to kill the "four pests" (sparrows, rats, insects and flies). Every person in China was issued a flyswatter and millions of flies were killed after Mao gave the directive "Away with all pests!" The fly problem persisted however. The writer Hu Yua recalls his doctor father wearing a bloodstained smock in a small one-room clinic across the street from his family house. Their home also faced a public toilet, where nurses often dumped tumors, and the local mortuary. On hot summer days, it was cool inside the mortuary, Yu recalled, and since the corpses were deposited only at night, I often took a nap there. Sleeping at night in our home, we would be woken by the sound of people crying. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

The writer Hu Yua recalls his doctor father wearing a bloodstained smock in a small one-room clinic across the street from his family house. Their home also faced a public toilet, where nurses often dumped tumors, and the local mortuary. On hot summer days, it was cool inside the mortuary, Yu recalled, and since the corpses were deposited only at night, I often took a nap there. Sleeping at night in our home, we would be woken by the sound of people crying. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]Barefoot Doctors

Doctors in the Mao era In the Mao era, around 1 million "barefoot doctors” were give six months of training and sent out to countryside to open rural clinics, provide immunizations and offer basic medical care. They often wore straw hats and carried small wooden medical boxes from their shoulder.

Doctors in the Mao era In the Mao era, around 1 million "barefoot doctors” were give six months of training and sent out to countryside to open rural clinics, provide immunizations and offer basic medical care. They often wore straw hats and carried small wooden medical boxes from their shoulder. Some of barefoot doctors only had an elementary school education. One 68-year-old man said he took an aptitude test on the suggestion of his mother. “They asked me, why does a train run so fast. I’d never seen a train before, so I racked my brain.”

Some of barefoot doctors only had an elementary school education. One 68-year-old man said he took an aptitude test on the suggestion of his mother. “They asked me, why does a train run so fast. I’d never seen a train before, so I racked my brain.” The barefoot doctors traditionally roamed the countryside, visiting around a dozen farmers a day, charging them a nominal registration fee and giving out medication for free. They didn’t do anything too complicated. One doctor told the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t treat serious illnesses. I don’t know how.”

The barefoot doctors traditionally roamed the countryside, visiting around a dozen farmers a day, charging them a nominal registration fee and giving out medication for free. They didn’t do anything too complicated. One doctor told the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t treat serious illnesses. I don’t know how.” The barefoot doctor tradition lives on in services such as the Lifeline Express, a train that operates in poor areas in Xinjiang Province and offers cataract surgery for free to all comers. The cataract operations take 15 to 20 minutes, involve cutting the cornea and replacing a clouded lens with a clear artificial one,. The operations given in an assembly line fashion to patients by doctors who put in 12 hour days and volunteer their services for little pay for one-year stints.

The barefoot doctor tradition lives on in services such as the Lifeline Express, a train that operates in poor areas in Xinjiang Province and offers cataract surgery for free to all comers. The cataract operations take 15 to 20 minutes, involve cutting the cornea and replacing a clouded lens with a clear artificial one,. The operations given in an assembly line fashion to patients by doctors who put in 12 hour days and volunteer their services for little pay for one-year stints. Although China's ‘barefoot doctors’ scheme relied on primitive supplies and under-trained doctors, it has been acknowledged by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the pioneering role it played in the development of China's rural primary healthcare.

Although China's ‘barefoot doctors’ scheme relied on primitive supplies and under-trained doctors, it has been acknowledged by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the pioneering role it played in the development of China's rural primary healthcare. Treatment by Barefoot Doctors

Describing the difficulty in bringing good medical care to rural areas in China, one barefoot doctor told the New York Times, "When we go out and try to inoculate babies, some peasants are very frightened and hide their kids. Or they turn their dogs on us to bite us and drive us away...We give them injections for measles, and then the kid gets a cold. So the parents come, and complain. They say, 'You promised that my child wouldn't get sick!'" The inoculations themselves are fairly easy to give to young children because many of them don’t wear pants or they wear pants purposely made with holes in them..

Describing the difficulty in bringing good medical care to rural areas in China, one barefoot doctor told the New York Times, "When we go out and try to inoculate babies, some peasants are very frightened and hide their kids. Or they turn their dogs on us to bite us and drive us away...We give them injections for measles, and then the kid gets a cold. So the parents come, and complain. They say, 'You promised that my child wouldn't get sick!'" The inoculations themselves are fairly easy to give to young children because many of them don’t wear pants or they wear pants purposely made with holes in them.. These days the doctors don’t roam so much any more. Each village has its own doctor. A typical rural clinic run by a barefoot doctor consists of a single room in mud-brick, thatch-roofed building or concrete, tin-roof structure with a couple of bamboo cots, a desk and wooden cupboard with some pain, fever, diarrhea, and cold medicines inside. It typically doesn’t have a phone but it does have disposable needles, an improvement from the old days when needles were reused after they were swabbed with alcohol.

These days the doctors don’t roam so much any more. Each village has its own doctor. A typical rural clinic run by a barefoot doctor consists of a single room in mud-brick, thatch-roofed building or concrete, tin-roof structure with a couple of bamboo cots, a desk and wooden cupboard with some pain, fever, diarrhea, and cold medicines inside. It typically doesn’t have a phone but it does have disposable needles, an improvement from the old days when needles were reused after they were swabbed with alcohol. Rural clinics typically have dirt floors and lack sterilizing equipment, Many of the medicines are fake but are sold by doctors anyway because the drugs are their primary source of income. Equipment consists of a thermometer and a blood pressure machine that doesn’t work. Wish lists by barefoot doctors include a stomach pump, tools for extracting abscessed teeth, and oxygen cannisters for respiratory problems.

Rural clinics typically have dirt floors and lack sterilizing equipment, Many of the medicines are fake but are sold by doctors anyway because the drugs are their primary source of income. Equipment consists of a thermometer and a blood pressure machine that doesn’t work. Wish lists by barefoot doctors include a stomach pump, tools for extracting abscessed teeth, and oxygen cannisters for respiratory problems. With the introduction of economic reforms and capitalism, money for public health has declined. Barefoot doctors see fewer people because their patients have to pay considerably more than they did in the old days and people get sicker less. One barefoot doctor told AP, "Now the job is easier because vaccinations have eliminated so many diseases, like measles."

With the introduction of economic reforms and capitalism, money for public health has declined. Barefoot doctors see fewer people because their patients have to pay considerably more than they did in the old days and people get sicker less. One barefoot doctor told AP, "Now the job is easier because vaccinations have eliminated so many diseases, like measles." One their most successful herbal medicines, pumpkin seeds, was used to rid victims of worms. Today the treatment is also used in Africa to combat schistosomiasis.

One their most successful herbal medicines, pumpkin seeds, was used to rid victims of worms. Today the treatment is also used in Africa to combat schistosomiasis. Pre- History of Barefoot Doctors

Alexander Casella wrote in the Asia Times, “When the communists come to power in China in 1949, the country had some 40,000 doctors for a population of some 540 million, which meant on average one doctor for some 13,500 inhabitants (the figure today is one for 950). The vast shortages in terms of numbers was compounded by another problem. Most of the doctors were in the cities and except for some practitioners of traditional medicine, the countryside was practically deprived of any real medical care and epidemics. This meant infectious diseases and poor sanitation were pervasive.”[Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009]

Alexander Casella wrote in the Asia Times, “When the communists come to power in China in 1949, the country had some 40,000 doctors for a population of some 540 million, which meant on average one doctor for some 13,500 inhabitants (the figure today is one for 950). The vast shortages in terms of numbers was compounded by another problem. Most of the doctors were in the cities and except for some practitioners of traditional medicine, the countryside was practically deprived of any real medical care and epidemics. This meant infectious diseases and poor sanitation were pervasive.”[Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009] “While many of its top leaders were of urban or semi-urban origin, the communist movement in China derived its strength from the fact that it had succeeded in mobilizing the peasantry in its support and, once in power, the party made rural healthcare one of its priorities.” [Ibid]

“While many of its top leaders were of urban or semi-urban origin, the communist movement in China derived its strength from the fact that it had succeeded in mobilizing the peasantry in its support and, once in power, the party made rural healthcare one of its priorities.” [Ibid] “With trained doctors in short supply, the central government in 1951 decided that basic healthcare in the countryside should be provided by health workers rather than by fully trained physicians. In 1957, there were more than 200,000 such ‘village doctors’ whose administration was under the responsibility of the local authorities. While these village doctors had received only basic training and could not treat complicated cases, their impact was considerable and especially so in preventing minor ills or wounds from developing into complex medical problems and in implementing nation-wide vaccination campaigns.” [Ibid]

“With trained doctors in short supply, the central government in 1951 decided that basic healthcare in the countryside should be provided by health workers rather than by fully trained physicians. In 1957, there were more than 200,000 such ‘village doctors’ whose administration was under the responsibility of the local authorities. While these village doctors had received only basic training and could not treat complicated cases, their impact was considerable and especially so in preventing minor ills or wounds from developing into complex medical problems and in implementing nation-wide vaccination campaigns.” [Ibid] Early History of Barefoot Doctors

“In 1968, the village doctor program was renamed ‘barefoot doctors’, with the name derived from southern farmers who would often work barefoot in the rice paddies. It was presented as one of the great achievements of the Cultural Revolution. Actually, it had been in force since long before but the rebranding suited the politics of the time. With millions of ‘educated youth’ sent to the countryside, the barefoot doctor scheme acquired an iconic dimension. Actually, it was nothing more than ideology on the rampage combined with a reform of the existing medical system, which now included an expansion of the short-term training program of village doctors.[Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009]

“In 1968, the village doctor program was renamed ‘barefoot doctors’, with the name derived from southern farmers who would often work barefoot in the rice paddies. It was presented as one of the great achievements of the Cultural Revolution. Actually, it had been in force since long before but the rebranding suited the politics of the time. With millions of ‘educated youth’ sent to the countryside, the barefoot doctor scheme acquired an iconic dimension. Actually, it was nothing more than ideology on the rampage combined with a reform of the existing medical system, which now included an expansion of the short-term training program of village doctors.[Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009] “Reducing the number of years of training for doctors, a policy that now applied to all university education - was very much an obsession with Mao Zedong. The chairman had a strong mistrust of doctors, including his own, and used to claim that six or more years of medical training were a waste of time and resources when one or two were sufficient. Given the state of China's economy at the time, this view was not totally misplaced except it was not derived from an objective analysis, but rather from a personal suspicion of the medical profession. If implemented, it would have set medicine backwards in China for decades.” [Ibid]

“Reducing the number of years of training for doctors, a policy that now applied to all university education - was very much an obsession with Mao Zedong. The chairman had a strong mistrust of doctors, including his own, and used to claim that six or more years of medical training were a waste of time and resources when one or two were sufficient. Given the state of China's economy at the time, this view was not totally misplaced except it was not derived from an objective analysis, but rather from a personal suspicion of the medical profession. If implemented, it would have set medicine backwards in China for decades.” [Ibid] “Nonetheless, the impetus it gave to overall rural healthcare was considerable. Even though the supplies provided to the barefoot doctors - generally a few medicines, some needles and syringes and not much else - was primitive. Therein lay the weakness of the system; it provided the rural poor with a level of healthcare unknown before the revolution, but was unable to develop beyond the requirements of the most basic of health needs.” [Ibid]

“Nonetheless, the impetus it gave to overall rural healthcare was considerable. Even though the supplies provided to the barefoot doctors - generally a few medicines, some needles and syringes and not much else - was primitive. Therein lay the weakness of the system; it provided the rural poor with a level of healthcare unknown before the revolution, but was unable to develop beyond the requirements of the most basic of health needs.” [Ibid] “Given, however, the requirements of China at the time, the flaws in the system were slight as opposed to the program's achievements, an accomplishment that was acknowledged by the declaration of Alma Ata of September 12, 1978, when a WHO-sponsored conference recognized China's achievements in public health as a milestone for Third World countries.”

“Given, however, the requirements of China at the time, the flaws in the system were slight as opposed to the program's achievements, an accomplishment that was acknowledged by the declaration of Alma Ata of September 12, 1978, when a WHO-sponsored conference recognized China's achievements in public health as a milestone for Third World countries.” Collapse of the Barefoot Doctor System

“Initially, the barefoot doctor scheme survived the Cultural Revolution and in 1980 the State Council directed that, after having passed an examination, barefoot doctors could qualify as village doctors. This was hoped to fill the gap in rural areas between primary needs provided by barefoot doctors and advanced healthcare provided by fully trained practitioners.” [Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009]

“Initially, the barefoot doctor scheme survived the Cultural Revolution and in 1980 the State Council directed that, after having passed an examination, barefoot doctors could qualify as village doctors. This was hoped to fill the gap in rural areas between primary needs provided by barefoot doctors and advanced healthcare provided by fully trained practitioners.” [Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009] “The rural health system started to collapse in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a result of China's economic liberalization and the privatization of agriculture. Local medical facilities that had been financed collectively by the communes lost their source of income and had to close down. This in turn led to a collapse of primary healthcare and inoculation facilities and the result was that many diseases that had been eradicated re-emerged in the countryside. Regarding hospitalization, the user-pays system introduced in the 1980s left many rural patients, practically all of whom had no health insurance, unable to pay for medical care, which led to a further decline in rural health standards.” [Ibid]

“The rural health system started to collapse in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a result of China's economic liberalization and the privatization of agriculture. Local medical facilities that had been financed collectively by the communes lost their source of income and had to close down. This in turn led to a collapse of primary healthcare and inoculation facilities and the result was that many diseases that had been eradicated re-emerged in the countryside. Regarding hospitalization, the user-pays system introduced in the 1980s left many rural patients, practically all of whom had no health insurance, unable to pay for medical care, which led to a further decline in rural health standards.” [Ibid] “While the authorities were not totally unaware of the collapse of the rural health system as a price to pay for de-collectivization, no systematic measures were taken to redress some of the downsides of economic reform. Indeed, in this field, like many others, the regime demonstrated its inability at implementing parallel policies rather than skipping from one priority to another. By the early 1990s, the government had not only done away with the constraints of collectivization, but had also, in the process, seen the collapse of the rural healthcare system. This was akin to throwing the baby out with the bath water.” [Ibid]

“While the authorities were not totally unaware of the collapse of the rural health system as a price to pay for de-collectivization, no systematic measures were taken to redress some of the downsides of economic reform. Indeed, in this field, like many others, the regime demonstrated its inability at implementing parallel policies rather than skipping from one priority to another. By the early 1990s, the government had not only done away with the constraints of collectivization, but had also, in the process, seen the collapse of the rural healthcare system. This was akin to throwing the baby out with the bath water.” [Ibid] Rural China Misses Barefoot Doctors

Today primary care, even in the cities, is almost non-existent and with no independent doctors or neighborhood clinics, people have to go to hospitals even for simple healthcare needs. With hospitals told to finance their own costs and 79 percent of the population having no health insurance, the burden on the average Chinese is considerable, with the result that many simply cannot afford any healthcare at all.” [Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009]

Today primary care, even in the cities, is almost non-existent and with no independent doctors or neighborhood clinics, people have to go to hospitals even for simple healthcare needs. With hospitals told to finance their own costs and 79 percent of the population having no health insurance, the burden on the average Chinese is considerable, with the result that many simply cannot afford any healthcare at all.” [Source: Alexander Casella, Asia Times, January 16, 2009] “The one to 950 ratio of doctors to the population appears encouraging, but it only reflects part of the picture. It compares favorably to one for 500 inhabitants in Japan, 400 in Australia and 300 in Western Europe as opposed to 1,700 in India and 50.000 in Tanzania. But these numbers don't reflect the fact that most of China's doctors are concentrated in the cities. Likewise, while most general hospitals are clearly below Western standards aside from a few specialized hospitals which routinely perform complex operations with well-trained doctors and the latest equipment. These are increasingly catering to the need of the newly affluent Chinese.” [Ibid]

“The one to 950 ratio of doctors to the population appears encouraging, but it only reflects part of the picture. It compares favorably to one for 500 inhabitants in Japan, 400 in Australia and 300 in Western Europe as opposed to 1,700 in India and 50.000 in Tanzania. But these numbers don't reflect the fact that most of China's doctors are concentrated in the cities. Likewise, while most general hospitals are clearly below Western standards aside from a few specialized hospitals which routinely perform complex operations with well-trained doctors and the latest equipment. These are increasingly catering to the need of the newly affluent Chinese.” [Ibid] “In a country where large swaths of the population do not have access to the most basic healthcare, it is this group which spends an estimated $2 billion a year on cosmetic surgery. This can only increase the gap between the haves and the have-nots. “ [Ibid]

“In a country where large swaths of the population do not have access to the most basic healthcare, it is this group which spends an estimated $2 billion a year on cosmetic surgery. This can only increase the gap between the haves and the have-nots. “ [Ibid] “According to current estimates, it would take half a million additional doctors, well distributed across the country, to provide the healthcare that the Chinese really need. This, however, would require not only additional training of doctors but also a reform of their status and remuneration. This would go a long way towards reducing the exodus of Chinese doctors, an increasing number of whom are now practicing in Africa, where they not only receive better wages but also have a higher social standing.”

“According to current estimates, it would take half a million additional doctors, well distributed across the country, to provide the healthcare that the Chinese really need. This, however, would require not only additional training of doctors but also a reform of their status and remuneration. This would go a long way towards reducing the exodus of Chinese doctors, an increasing number of whom are now practicing in Africa, where they not only receive better wages but also have a higher social standing.” “According to Western medical sources, the Chinese government is coming to realize that it needs to address what could develop into a major health crisis in rural areas, but there remains a large question mark over what priority they have set for this and how they plan to address it.”

“According to Western medical sources, the Chinese government is coming to realize that it needs to address what could develop into a major health crisis in rural areas, but there remains a large question mark over what priority they have set for this and how they plan to address it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment